Portugal’s green‑and‑red flag was introduced in 1911 after the 5 October 1910 republican revolution, replacing the royal blue‑white. Centered over the color boundary is the armillary sphere—evoking the Age of Discoveries—charged with the national shield (Order of Christ cross, five quinas, seven castles). Green stands for hope; red recalls sacrifice for the republic.

Portugal’s green‑and‑red national flag crystallized out of the 1910 revolution that overthrew the Braganza monarchy and announced a republican order. Adopted by decree in 1911, the design rejected the royal blue‑white while retaining, at its core, heraldic and maritime emblems that narrate a millennium of Portuguese statehood.

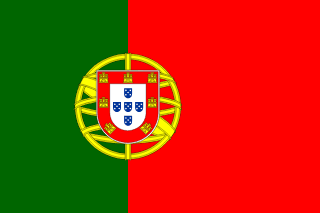

Immediately after the 5 October 1910 uprising, the provisional government tasked a commission—including painter Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, politician‑journalist João Chagas, and writer Abel Botelho—with proposing a national flag. Their solution was a vertical bicolour: green at the hoist occupying two‑fifths of the length and red at the fly occupying three‑fifths, a 2:3 overall ratio. Centered over the color boundary sits a golden armillary sphere charged with the national shield composed of the five blue escutcheons (quinas) dotted with silver bezants, bordered by seven golden castles on red. The decree of 30 June 1911 codified dimensions, placement, and color references that later guidance refined for print and fabric.

The palette took on powerful republican meanings. Red was presented as the blood shed by those who fought for freedom and as the energy of national renewal; green, long used by republican movements and the Carbonária, was framed as the hope of the nation. These political readings joined older associations with the sea and navigation that the armillary sphere foregrounded. The sphere—used by mariners and astronomers—had entered Portuguese heraldry centuries earlier, notably under King João VI, and by 1911 it symbolized the Age of Discoveries, scientific ambition, and a global horizon.

The shield preserves medieval symbolism at the flag’s heart. The quinas arranged in a cross recall the five wounds of Christ and, by legend, King Afonso I’s victory at Ourique; the bezants refer to miraculous coins or captured tribute. The surrounding red border with seven castles commemorates territorial consolidation in the thirteenth century under Afonso III. Topped in modern arms by the royal crown under monarchy and later replaced by the mural crown in certain civic contexts, the shield on the national flag remains uncrowned, reflecting republican legitimacy while honoring historic sovereignty.

Under the Estado Novo (1933–1974), the flag remained unchanged even as the regime invested it with authoritarian ritual. Strict etiquette governed display on public buildings, schools, and military installations; flag desecration incurred penalties that, in softened form, survive in modern law. After the Carnation Revolution of 1974 restored democracy, continuity prevailed: the 1911 flag, decoupled from authoritarian ideology, served as a stable symbol bridging monarchy’s end, dictatorship’s fall, and a European democratic future.

Specifications

today maintain the 2:3 ratio, the 2/5–3/5 vertical division, and precise relationships between the armillary sphere and the shield. Technical standards reference Pantone Green 349 C and Red 485 C (or equivalent CMYK/RGB) to harmonize production. The sphere’s center lies on the boundary between green and red, and its diameter is fixed relative to the flag’s height to ensure visual balance. Manufacturers must respect these constraints to avoid distortions of the emblem or crowding at the edges.

Protocol

prescribes respectful handling: the flag should be hoisted at sunrise, lowered at sunset unless illuminated, and never touch the ground. On national holidays—particularly Portugal Day (10 June)—and at international events, the flag appears alongside the European Union flag and other national flags, always with Portuguese precedence on government premises. Half‑masting follows formal orders of the Council of Ministers. Indoors, a fringed ceremonial flag may be used for processions and guard mounts; outdoors, flags are unfringed.

Interpretations continue to intertwine republican ideals with oceanic memory. Green symbolizes hope and civic aspiration; red signals courage and sacrifice. The armillary sphere points to a scientific and exploratory past and to Portugal’s historic maritime networks, while the shield’s quinas and castles speak to medieval origins and territorial defense. The composition’s placement—emblem astride the color boundary—has been read as a bridge between old and new, monarchy and republic, continental homeland and overseas missions.

From the blue‑white monarchic banners to the green‑red of 1911, Portuguese vexillology traces the nation’s changing self‑understanding. Yet the decision to keep the armillary sphere and shield reveals a through‑line: rather than severing the past, the Republic re‑framed it within a civic narrative. That synthesis, encoded in ratios and heraldry, makes the Bandeira Nacional a compact history lesson: a medieval kingdom turned ocean‑spanning empire turned modern European democracy, confident enough to carry symbols of each era on a single cloth.